Ely. UK

Motivation and mindset anchoring.

When I was at University, a

running joke was how little we’d all worked on our papers,

how late and last minute we’d

left them, and how little effort we’d put into them.

A couple of things jolted me

out of this mindset. International students I knew, from China,

India, Europe, Africa and

South America, didn’t seem to share English students’ view

that slack effort was funny

and clever. And my Dad told me that what actually happened

at his University was that

people boasted publicly about not working,

but then worked feverishly in

private. The joke was on us.

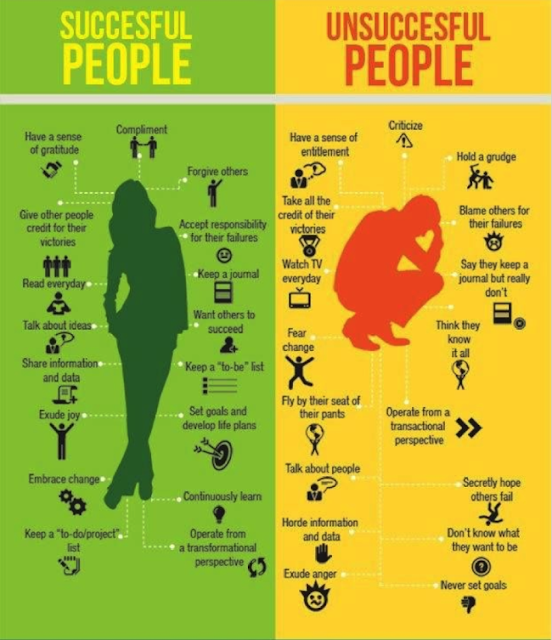

Beliefs matter; mindset

matters; work ethic matters.

Kids’ ideas about effort stem

from their mindset. The research from Carol Dweck is much acclaimed, and

rightly so. If you believe in effortless intelligence, it leads to fear of

effort and failure.

If you believe in hard work

and overcoming setbacks, this leads to success.

Mindsets change the meaning

of embarrassing mistakes, tough challenges, hurtful setbacks, negative

criticism and long slogs into opportunities. They internalise the questions:

‘What

can I learn from this? What can I do to improve for next time?’

So a vital ingredient in the

motivation mix is the belief kids bring to lessons in their minds.

Either they believe hard work

leads to success, or they don’t.

If they don’t, they’ll avoid

challenge and give up easily when failing. If they believe their intelligence

grows with practice, effort and discipline, they’ll seek challenge and persist

when failing.

The promise of the growth

mindset is that kids no longer see tough, challenging work

as long or

boring: they ‘not only seek challenge, they thrive on it’…

‘Students

with the growth mindset completely took charge of their learning and

motivation.’

Perhaps the best way to

understand this is through a scenario. What would you do in this scenario?

You’ve coached a student debating team all year through practice debates.

Your team is strong and aim

to win the annual competition against other schools.

They’ve even imagined taking

the trophy home. In the event, your team starts strong

but is defeated on points.

They are devastated. How would you react as their coach?

Tell them you thought they

were best

Tell them they were robbed of

the trophy

Tell them debating isn’t that

important in the grand scheme of things

Tell them they have the

ability and will surely win next time

Tell them they didn’t deserve

to win

Now, which did you choose?

Dwek argues that choices 1-4

don’t help them improve. Instead, she recommends 5:

‘I know how you feel. It’s

disappointing to do your best but not win.

But you haven’t earned it yet.

The other teams have practiced harder.

If you really want this, it’s

something you’ll have to really work for.’

This reveals that you choose

your mindset; it’s a choice within everyone’s sphere of control.

And that brings me on to

choice architecture.

In their book Nudge,

Thaler and Sunstein make the

case for us to think about ourselves as choice architects:

‘Choice architects have

responsibility for organising the context in which people make decisions.

People’s decisions are pervasively, unavoidably and greatly influenced by the

design elements selected by choice architects.’

One of the most important

choices we are responsible for as teachers and school leaders,

is organising the context

around the decision every pupil makes on every task in every lesson:

‘do I make the effort on this, or not bother?’

One of the greatest design

tools a choice architect is understanding cognitive biases.

A comprehensive list of fifty

is available in the book, The Art of Thinking Clearly:

One of the greatest cognitive

biases in pupils’ minds is status quo bias, or the default effect.

Inertia is sticky: we tend to

go with the status quo. Here’s how Thaler and Sunstein explain it:

‘Status quo bias is the preference for inertia.

Research shows that whatever

the default choice is, many people stick with it.

Teachers know students tend to

sit in the same seats in class, even without a seating plan.

‘The default option is

perceived as the normal choice; deviating from the normal choice

requires more effortful

deliberation and take on more responsibility.

These powerful forces guide the

decisions of those otherwise unsure of what to do.

‘Never underestimate the power

of inertia. That power can be harnessed’.

An excellent example is organ

donations. There’s a shortage of organ donors:

only about 40% of people opt

for it. But when asked whether people wanted to actively opt-out

of organ donation, the

take-up increased to 80%. Opt-outs as default options are powerful.

Because we have such a strong

tendency to stick with the way things are,

by changing the default

setting, you can change a lot.

Behavioural economists and

cognitive psychologists are finding how much anchoring matters. Anchoring

guides and constrains our thinking. Once your mind is hooked onto the anchor,

it’s much harder to stray

away from it.

Kahnemann in Thinking Fast and Slowgives

this demonstration:

‘What if I said Gandhi was 144

when he died, then asked you, how old was Gandhi

when he died?’ People’s average answer was over 100; in reality, Gandhi

died at 79.

The unreasonably high anchor

hooked them in to a higher number than was probable.

Combined, the promise of the

growth mindset with the effect of anchoring, the default option

and status quo bias could be

powerful for increasing pupil motivation in schools.

So how do we anchor the

growth mindset on challenge, effort and setbacks as the default option?

Senior leaders

Teach the message that all

our teachers and pupils choose a growth mindset,

from the moment kids enter

school onwards; that’s ‘just the way things are done

around here’

Share mindset stories of how setbacks, failures and practice

led to eventual success

Practise scenarios in teacher training on challenges,

praise, criticism and setbacks

Teachers

Teach the science:

challenges, practice, effort, self-discipline, mistakes,

setbacks and feedback are the

keys to improving intelligence and successful learning

Model the mindset: share

anecdotes of persistence, share frustrations and acknowledge mistakes, keep

asking ‘what can we do to improve for next time?’

Contrast and correct fixed

mindset mentalities and expressions with ways to think more productively about

things when they get tough: ‘You’re in charge of your mind.

You can help it grow strong by

using it in the right way’

How would you know when a

school has succeeded in growth mindset?

I’d argue that when it’s

become the default option for every pupil,

the school is on autopilot to

achievement.

You’d go in to any classroom

at any time and every kid would be on task on every task.

Motivation isn’t just up to

school leaders and teachers, though.

Over the next two weeks I’ll

consider the crucial roles peer pressure

and parental priming play in

anchoring the growth mindset as the default option.

https://pragmaticreform.wordpress.com/2014/06/07/motivation-and-mindset-anchoring/

You can TCR software and engineering manuals for spontaneously recall – or pass that exam.

I can Turbo Charge Read a novel 6-7 times faster and remember what

I’ve read.

I can TCR an instructional/academic book around 20 times faster and remember what I’ve

read.

A practical overview of Turbo Charged Reading YouTube

How

to choose a book. A Turbo Charged Reading YouTube

Advanced Reading Skills Perhaps you’d like

to join my FaceBook group ?

Perhaps you’d like to check

out my sister blogs:

www.innermindworking.blogspot.com

gives many ways for you to work with the stresses of

life

www.ourinnerminds.blogspot.com

take advantage of business experience and expertise.

www.happyartaccidents.blogspot.com

just for fun.

To quote the Dr Seuss

himself, “The more that you read, the more things you will know.

The more that you learn; the

more places you'll go.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your opinions, experience and questions are welcome. M'reen